Caroline Stauffer is a member of the core SIPA Team deploying the Ushahidi-Chile platform. She is a graduate student at Columbia University's School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) where she focuses on International Media and Communications. She spent the past summer working with the Associated Press in Bangkok, and worked for a nongovernmental organization in the Dominican Republic prior to SIPA.

Continuous aftershocks, office buildings scheduled for destruction, villages without access to water, gasoline shortages, and looting. These are some of the 800+ incidents my fellow students and I mapped during our first week in the situation room at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA). The death toll from the February 27 earthquake is much lower than the number of lives lost since January 12 in Haiti, but the 8.8-magnitude quake in southern Chile was one of the largest on record, and coordinating information, needs and responses on the ground is essential.

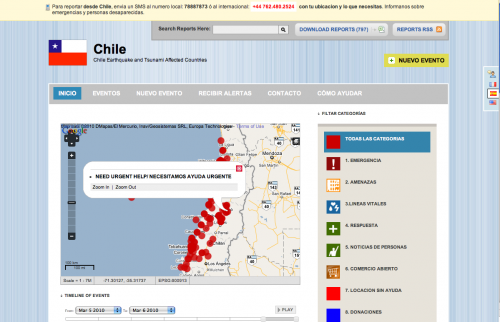

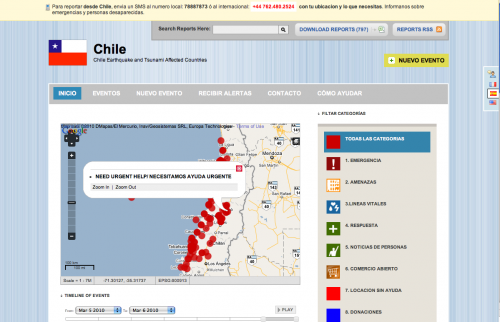

[caption id="attachment_1628" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="Near real-time crisis mapping"] [/caption]

An initial training session at Columbia University the Monday after the earthquake drew 60 students—during SIPA’s midterm examination period. A core team of six students is working to ensure that the growing list of volunteer names translates into more hours spent monitoring and mapping. Other schools within Columbia University are starting to get involved, and the team has reached out to contacts at New York University. One of our core members took a quick break from the Situation Room to head to United Nations headquarters after individuals from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) asked for training on the Ushahidi-Chile application. Most importantly, as students continue to monitor traditional and social media, more reports are reaching the Ushahidi platform from on the ground in Chile.

[caption id="attachment_1630" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="The core SIPA Team"]

[/caption]

An initial training session at Columbia University the Monday after the earthquake drew 60 students—during SIPA’s midterm examination period. A core team of six students is working to ensure that the growing list of volunteer names translates into more hours spent monitoring and mapping. Other schools within Columbia University are starting to get involved, and the team has reached out to contacts at New York University. One of our core members took a quick break from the Situation Room to head to United Nations headquarters after individuals from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) asked for training on the Ushahidi-Chile application. Most importantly, as students continue to monitor traditional and social media, more reports are reaching the Ushahidi platform from on the ground in Chile.

[caption id="attachment_1630" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="The core SIPA Team"] [/caption]

Some students were initially skeptical of Ushahidi-Chile. The Chilean government had said international aid was not necessary, and the value of mapping information from news sources and Twitter—in short, information that can be found elsewhere—was questioned. However, by Monday, messages communicating the needs and locations of people who lacked basic supplies and water were coming in. It seemed that our team had uploaded enough information to be truly useful on the ground. Soon, Chilean organizations including Red Salvavidas and Chile Ayuda were contributing reports daily.

As a journalist, the flow of information within Ushahidi has been immensely interesting to me. The process that our teams of monitors, mappers and administrators go through to produce the Ushahidi page is not unlike the path a journalist takes to report and produce a story. In both cases, the reporter seeks information from overlooked sources and tries to verify the data. Small bits of information combine to produce a larger picture, giving an overview of a particular situation. In Ushahidi, the picture that emerges is an interactive map, rather than a narrated story.

[caption id="attachment_1629" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="Crisis Mapping volunteers at SIPA"]

[/caption]

Some students were initially skeptical of Ushahidi-Chile. The Chilean government had said international aid was not necessary, and the value of mapping information from news sources and Twitter—in short, information that can be found elsewhere—was questioned. However, by Monday, messages communicating the needs and locations of people who lacked basic supplies and water were coming in. It seemed that our team had uploaded enough information to be truly useful on the ground. Soon, Chilean organizations including Red Salvavidas and Chile Ayuda were contributing reports daily.

As a journalist, the flow of information within Ushahidi has been immensely interesting to me. The process that our teams of monitors, mappers and administrators go through to produce the Ushahidi page is not unlike the path a journalist takes to report and produce a story. In both cases, the reporter seeks information from overlooked sources and tries to verify the data. Small bits of information combine to produce a larger picture, giving an overview of a particular situation. In Ushahidi, the picture that emerges is an interactive map, rather than a narrated story.

[caption id="attachment_1629" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="Crisis Mapping volunteers at SIPA"] [/caption]

The SIPA team has touched base with technology students from Talca, in one of the hardest regions hit in Chile. The Chilean students now have administrative abilities on the Ushahidi-Chile page. The goal of the SIPA students working with Chile-Ushahidi is to transfer the platform to an organization in Chile by the end of March, but to leave behind a trained group of crisis mappers at SIPA who will be ready to assemble and share information whenever and wherever the next disaster strikes.

[/caption]

The SIPA team has touched base with technology students from Talca, in one of the hardest regions hit in Chile. The Chilean students now have administrative abilities on the Ushahidi-Chile page. The goal of the SIPA students working with Chile-Ushahidi is to transfer the platform to an organization in Chile by the end of March, but to leave behind a trained group of crisis mappers at SIPA who will be ready to assemble and share information whenever and wherever the next disaster strikes.

[/caption]

An initial training session at Columbia University the Monday after the earthquake drew 60 students—during SIPA’s midterm examination period. A core team of six students is working to ensure that the growing list of volunteer names translates into more hours spent monitoring and mapping. Other schools within Columbia University are starting to get involved, and the team has reached out to contacts at New York University. One of our core members took a quick break from the Situation Room to head to United Nations headquarters after individuals from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) asked for training on the Ushahidi-Chile application. Most importantly, as students continue to monitor traditional and social media, more reports are reaching the Ushahidi platform from on the ground in Chile.

[caption id="attachment_1630" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="The core SIPA Team"]

[/caption]

An initial training session at Columbia University the Monday after the earthquake drew 60 students—during SIPA’s midterm examination period. A core team of six students is working to ensure that the growing list of volunteer names translates into more hours spent monitoring and mapping. Other schools within Columbia University are starting to get involved, and the team has reached out to contacts at New York University. One of our core members took a quick break from the Situation Room to head to United Nations headquarters after individuals from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) asked for training on the Ushahidi-Chile application. Most importantly, as students continue to monitor traditional and social media, more reports are reaching the Ushahidi platform from on the ground in Chile.

[caption id="attachment_1630" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="The core SIPA Team"] [/caption]

Some students were initially skeptical of Ushahidi-Chile. The Chilean government had said international aid was not necessary, and the value of mapping information from news sources and Twitter—in short, information that can be found elsewhere—was questioned. However, by Monday, messages communicating the needs and locations of people who lacked basic supplies and water were coming in. It seemed that our team had uploaded enough information to be truly useful on the ground. Soon, Chilean organizations including Red Salvavidas and Chile Ayuda were contributing reports daily.

As a journalist, the flow of information within Ushahidi has been immensely interesting to me. The process that our teams of monitors, mappers and administrators go through to produce the Ushahidi page is not unlike the path a journalist takes to report and produce a story. In both cases, the reporter seeks information from overlooked sources and tries to verify the data. Small bits of information combine to produce a larger picture, giving an overview of a particular situation. In Ushahidi, the picture that emerges is an interactive map, rather than a narrated story.

[caption id="attachment_1629" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="Crisis Mapping volunteers at SIPA"]

[/caption]

Some students were initially skeptical of Ushahidi-Chile. The Chilean government had said international aid was not necessary, and the value of mapping information from news sources and Twitter—in short, information that can be found elsewhere—was questioned. However, by Monday, messages communicating the needs and locations of people who lacked basic supplies and water were coming in. It seemed that our team had uploaded enough information to be truly useful on the ground. Soon, Chilean organizations including Red Salvavidas and Chile Ayuda were contributing reports daily.

As a journalist, the flow of information within Ushahidi has been immensely interesting to me. The process that our teams of monitors, mappers and administrators go through to produce the Ushahidi page is not unlike the path a journalist takes to report and produce a story. In both cases, the reporter seeks information from overlooked sources and tries to verify the data. Small bits of information combine to produce a larger picture, giving an overview of a particular situation. In Ushahidi, the picture that emerges is an interactive map, rather than a narrated story.

[caption id="attachment_1629" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="Crisis Mapping volunteers at SIPA"] [/caption]

The SIPA team has touched base with technology students from Talca, in one of the hardest regions hit in Chile. The Chilean students now have administrative abilities on the Ushahidi-Chile page. The goal of the SIPA students working with Chile-Ushahidi is to transfer the platform to an organization in Chile by the end of March, but to leave behind a trained group of crisis mappers at SIPA who will be ready to assemble and share information whenever and wherever the next disaster strikes.

[/caption]

The SIPA team has touched base with technology students from Talca, in one of the hardest regions hit in Chile. The Chilean students now have administrative abilities on the Ushahidi-Chile page. The goal of the SIPA students working with Chile-Ushahidi is to transfer the platform to an organization in Chile by the end of March, but to leave behind a trained group of crisis mappers at SIPA who will be ready to assemble and share information whenever and wherever the next disaster strikes.