I recently had the distinct pleasure of giving a Keynote on "Freedom of Speech 2.0" at a conference on Human Rights and New Media in The Hague. I was very impressed with how the organizers of this superb conference managed to pull through in spite of the havoc caused by the volcano in Iceland. They took this an opportunity to demonstrate the application of new technologies to run part of the conference on Skype and other tools. So congratulations to the entire conference team for their pro-active, can-do attitude.

I kicked off the presentation by asking the following: "What do martians, Tom & Jerry and Venice have to do with Freedom of Speech 2.0?" An unlikely way to start, I admit.

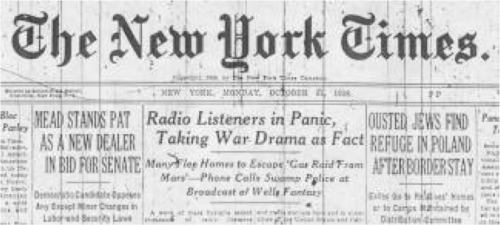

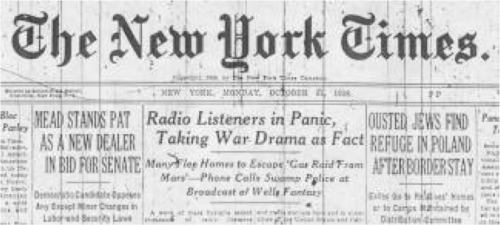

But lets take our Martian friends. You may recall H.G. Well's "War of the Worlds" drama about a Martian invasion of planet earth. The story was read as a radio broadcast in 1938 using a series of simulated news bulletins. The radio station ran no commercials during the broadcast which prompted many listeners in the US to believe an actual invasion was taking place. The panic this caused even made it to the front page of the New York Times:

But lets take our Martian friends. You may recall H.G. Well's "War of the Worlds" drama about a Martian invasion of planet earth. The story was read as a radio broadcast in 1938 using a series of simulated news bulletins. The radio station ran no commercials during the broadcast which prompted many listeners in the US to believe an actual invasion was taking place. The panic this caused even made it to the front page of the New York Times:

How was this possible? The information ecosystem in the 1930s was not only sparse but also mainly broadcast—one to many. Not particularly democratic compared to today's information ecosystem which facilitates a considerable amount of user-generated content. The ecosystem we're used to looks something like the graphic below. Not only are there more platforms but these are increasingly interconnected and interoperable. This makes the freedom of speech 2.0 possible.

How was this possible? The information ecosystem in the 1930s was not only sparse but also mainly broadcast—one to many. Not particularly democratic compared to today's information ecosystem which facilitates a considerable amount of user-generated content. The ecosystem we're used to looks something like the graphic below. Not only are there more platforms but these are increasingly interconnected and interoperable. This makes the freedom of speech 2.0 possible.

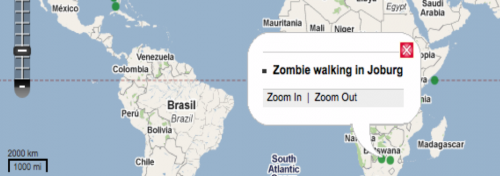

The Ushahidi platform is a tool that facilitates the aggregation of information across many of the technologies displayed above. In Kenya, where the platform was first used to document the post-election violence, Ushahidi aggregated information coming from SMS, web forms, social media and mainstream news. Individuals in Kenya could text a dedicated short code number to report any violence they had witnessed.

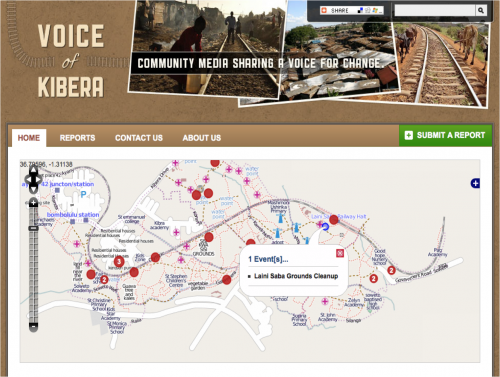

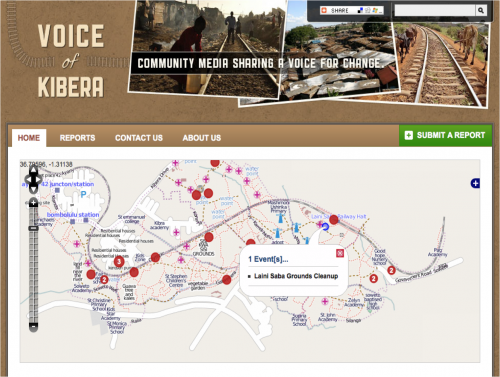

The platform has since been deployed by partners around the world. At it's heart, the platform allows users to increase transparency and accountability, and to improve coordination in a more distributed, democratic manner. One of the most recent deployments of Ushahidi is MapKibera, a project run by our good friends over at OpenStreetMap. MapKibera gives voice to people who don't necessarily enjoy freedom of Speech 1.0 to begin with.

The Ushahidi platform is a tool that facilitates the aggregation of information across many of the technologies displayed above. In Kenya, where the platform was first used to document the post-election violence, Ushahidi aggregated information coming from SMS, web forms, social media and mainstream news. Individuals in Kenya could text a dedicated short code number to report any violence they had witnessed.

The platform has since been deployed by partners around the world. At it's heart, the platform allows users to increase transparency and accountability, and to improve coordination in a more distributed, democratic manner. One of the most recent deployments of Ushahidi is MapKibera, a project run by our good friends over at OpenStreetMap. MapKibera gives voice to people who don't necessarily enjoy freedom of Speech 1.0 to begin with.

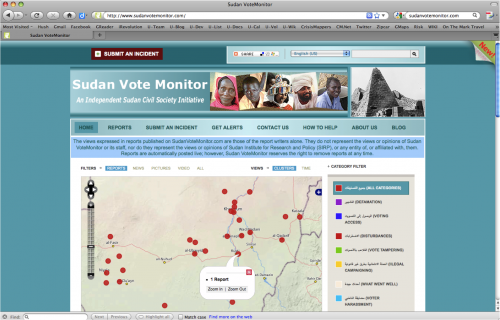

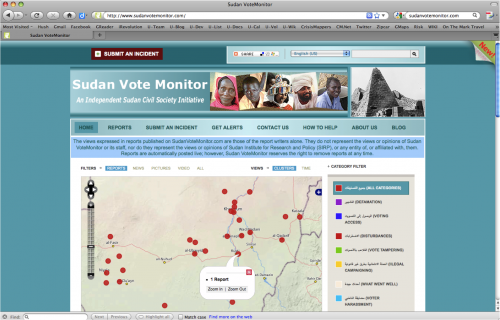

So that explains what Martians have to do with Freedom of Speech 2.0—at least indirectly! Next is Tom & Jerry, the cartoon. With Freedom of Speech 2.0 comes Repression of Speech 2.0. In other words, a cyber game of cat-and-mouse quickly evolves between those seeking more ways to express themselves and state officials who see this as a direct threat. One recent example of this dynamic is the SudanVoteMonitor project which was run by Sudanese civil society organizations. Apparently, the site was blocked a couple days into the elections. The group found another way to get the site back up within a few hours.

So that explains what Martians have to do with Freedom of Speech 2.0—at least indirectly! Next is Tom & Jerry, the cartoon. With Freedom of Speech 2.0 comes Repression of Speech 2.0. In other words, a cyber game of cat-and-mouse quickly evolves between those seeking more ways to express themselves and state officials who see this as a direct threat. One recent example of this dynamic is the SudanVoteMonitor project which was run by Sudanese civil society organizations. Apparently, the site was blocked a couple days into the elections. The group found another way to get the site back up within a few hours.

So it's clear that in non-permissive environments, there will be push back on Freedom of Speech 2.0. The key is to recognize that both technologies and tactics are important when communicating in repressive environments. Technologies alone won't circumvent repression 2.0. One of the tactics commonly used, for example, is to use code for the indicators being monitored, eg, 1 = fraud. There are many more which you can read up on here.

If this cat-and-mouse game continues, perhaps repressive regimes will come to see the futility of trying to censor or block certain websites—much like the music industry vis-a-vis the likes of Napster, e-Mule, etc. So if censorship becomes more difficult, then perhaps launching campaigns of disinformation may be the way to go for authoritarian states; this would dilute attempts at Freedom of Speech 2.0. Open crowdsourcing platforms like Ushahidi are certainly susceptible to misinformation. There's an obvious trade-off: open up entirely, and get more crowdsourced information, but run the risk of some clowns gaming the platform.

So it's clear that in non-permissive environments, there will be push back on Freedom of Speech 2.0. The key is to recognize that both technologies and tactics are important when communicating in repressive environments. Technologies alone won't circumvent repression 2.0. One of the tactics commonly used, for example, is to use code for the indicators being monitored, eg, 1 = fraud. There are many more which you can read up on here.

If this cat-and-mouse game continues, perhaps repressive regimes will come to see the futility of trying to censor or block certain websites—much like the music industry vis-a-vis the likes of Napster, e-Mule, etc. So if censorship becomes more difficult, then perhaps launching campaigns of disinformation may be the way to go for authoritarian states; this would dilute attempts at Freedom of Speech 2.0. Open crowdsourcing platforms like Ushahidi are certainly susceptible to misinformation. There's an obvious trade-off: open up entirely, and get more crowdsourced information, but run the risk of some clowns gaming the platform.

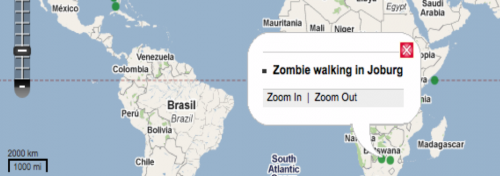

But I'd like to argue that falsifying crowdsourced information is perhaps not as easy as one might think, particularly in today's ecosystem where multiple witnesses can report on unfolding events in near real-time. The picture below is a good illustration of this ecosystem in action.

But I'd like to argue that falsifying crowdsourced information is perhaps not as easy as one might think, particularly in today's ecosystem where multiple witnesses can report on unfolding events in near real-time. The picture below is a good illustration of this ecosystem in action.

The fact that crowdsourcing can generate a lot of information is a distinct asset, and one that can be used to weed out disinformation. Take the screenshot below of the Ushahidi-Haiti deployment.

The fact that crowdsourcing can generate a lot of information is a distinct asset, and one that can be used to weed out disinformation. Take the screenshot below of the Ushahidi-Haiti deployment.

Multiple witnesses can be using different technologies to provide a better picture of what is actually happening. The different text messages, pictures, tweets, etc, can be triangulated and validated when they overlap. This prompted my colleague Anand from the New York Times to ask whether the triangulated crisis map might be the new first draft of history? They say that history is written by the winners. Will future history be written by the crowd thanks to Freedom of Speech 2.0?

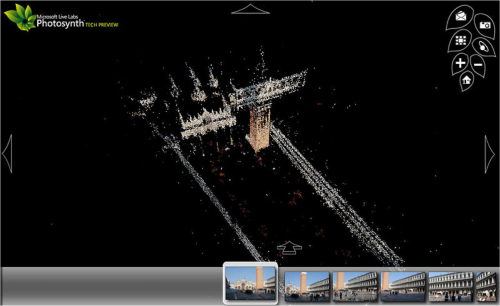

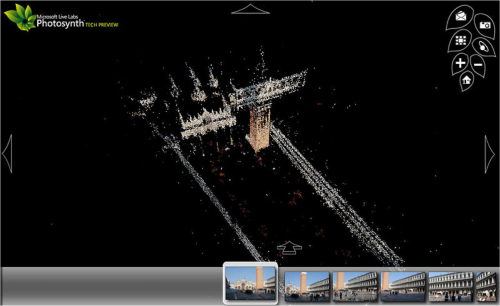

The above graphic reminds me of Photosynth, which is a neat platform that stitches pictures together to form an overall tableau. This is where Venice comes in. Taking pictures from Flickr or other sources, one can veritably recreate Venice in 3D. Really great stuff. So the question I posed during my TEDx talk last week is, can Ushahidi become the ALLsynth to facilitate Freedom of Speech 2.0? Can we crowdsource crisis information across diverse media and stitch these together to recreate what truly happened—not just over space but across time as well?

Multiple witnesses can be using different technologies to provide a better picture of what is actually happening. The different text messages, pictures, tweets, etc, can be triangulated and validated when they overlap. This prompted my colleague Anand from the New York Times to ask whether the triangulated crisis map might be the new first draft of history? They say that history is written by the winners. Will future history be written by the crowd thanks to Freedom of Speech 2.0?

The above graphic reminds me of Photosynth, which is a neat platform that stitches pictures together to form an overall tableau. This is where Venice comes in. Taking pictures from Flickr or other sources, one can veritably recreate Venice in 3D. Really great stuff. So the question I posed during my TEDx talk last week is, can Ushahidi become the ALLsynth to facilitate Freedom of Speech 2.0? Can we crowdsource crisis information across diverse media and stitch these together to recreate what truly happened—not just over space but across time as well?

And if we could, what would it take to game the Ushahidi ALLsynth system?

And if we could, what would it take to game the Ushahidi ALLsynth system?

But lets take our Martian friends. You may recall H.G. Well's "War of the Worlds" drama about a Martian invasion of planet earth. The story was read as a radio broadcast in 1938 using a series of simulated news bulletins. The radio station ran no commercials during the broadcast which prompted many listeners in the US to believe an actual invasion was taking place. The panic this caused even made it to the front page of the New York Times:

But lets take our Martian friends. You may recall H.G. Well's "War of the Worlds" drama about a Martian invasion of planet earth. The story was read as a radio broadcast in 1938 using a series of simulated news bulletins. The radio station ran no commercials during the broadcast which prompted many listeners in the US to believe an actual invasion was taking place. The panic this caused even made it to the front page of the New York Times:

How was this possible? The information ecosystem in the 1930s was not only sparse but also mainly broadcast—one to many. Not particularly democratic compared to today's information ecosystem which facilitates a considerable amount of user-generated content. The ecosystem we're used to looks something like the graphic below. Not only are there more platforms but these are increasingly interconnected and interoperable. This makes the freedom of speech 2.0 possible.

How was this possible? The information ecosystem in the 1930s was not only sparse but also mainly broadcast—one to many. Not particularly democratic compared to today's information ecosystem which facilitates a considerable amount of user-generated content. The ecosystem we're used to looks something like the graphic below. Not only are there more platforms but these are increasingly interconnected and interoperable. This makes the freedom of speech 2.0 possible.

The Ushahidi platform is a tool that facilitates the aggregation of information across many of the technologies displayed above. In Kenya, where the platform was first used to document the post-election violence, Ushahidi aggregated information coming from SMS, web forms, social media and mainstream news. Individuals in Kenya could text a dedicated short code number to report any violence they had witnessed.

The platform has since been deployed by partners around the world. At it's heart, the platform allows users to increase transparency and accountability, and to improve coordination in a more distributed, democratic manner. One of the most recent deployments of Ushahidi is MapKibera, a project run by our good friends over at OpenStreetMap. MapKibera gives voice to people who don't necessarily enjoy freedom of Speech 1.0 to begin with.

The Ushahidi platform is a tool that facilitates the aggregation of information across many of the technologies displayed above. In Kenya, where the platform was first used to document the post-election violence, Ushahidi aggregated information coming from SMS, web forms, social media and mainstream news. Individuals in Kenya could text a dedicated short code number to report any violence they had witnessed.

The platform has since been deployed by partners around the world. At it's heart, the platform allows users to increase transparency and accountability, and to improve coordination in a more distributed, democratic manner. One of the most recent deployments of Ushahidi is MapKibera, a project run by our good friends over at OpenStreetMap. MapKibera gives voice to people who don't necessarily enjoy freedom of Speech 1.0 to begin with.

So that explains what Martians have to do with Freedom of Speech 2.0—at least indirectly! Next is Tom & Jerry, the cartoon. With Freedom of Speech 2.0 comes Repression of Speech 2.0. In other words, a cyber game of cat-and-mouse quickly evolves between those seeking more ways to express themselves and state officials who see this as a direct threat. One recent example of this dynamic is the SudanVoteMonitor project which was run by Sudanese civil society organizations. Apparently, the site was blocked a couple days into the elections. The group found another way to get the site back up within a few hours.

So that explains what Martians have to do with Freedom of Speech 2.0—at least indirectly! Next is Tom & Jerry, the cartoon. With Freedom of Speech 2.0 comes Repression of Speech 2.0. In other words, a cyber game of cat-and-mouse quickly evolves between those seeking more ways to express themselves and state officials who see this as a direct threat. One recent example of this dynamic is the SudanVoteMonitor project which was run by Sudanese civil society organizations. Apparently, the site was blocked a couple days into the elections. The group found another way to get the site back up within a few hours.

So it's clear that in non-permissive environments, there will be push back on Freedom of Speech 2.0. The key is to recognize that both technologies and tactics are important when communicating in repressive environments. Technologies alone won't circumvent repression 2.0. One of the tactics commonly used, for example, is to use code for the indicators being monitored, eg, 1 = fraud. There are many more which you can read up on here.

If this cat-and-mouse game continues, perhaps repressive regimes will come to see the futility of trying to censor or block certain websites—much like the music industry vis-a-vis the likes of Napster, e-Mule, etc. So if censorship becomes more difficult, then perhaps launching campaigns of disinformation may be the way to go for authoritarian states; this would dilute attempts at Freedom of Speech 2.0. Open crowdsourcing platforms like Ushahidi are certainly susceptible to misinformation. There's an obvious trade-off: open up entirely, and get more crowdsourced information, but run the risk of some clowns gaming the platform.

So it's clear that in non-permissive environments, there will be push back on Freedom of Speech 2.0. The key is to recognize that both technologies and tactics are important when communicating in repressive environments. Technologies alone won't circumvent repression 2.0. One of the tactics commonly used, for example, is to use code for the indicators being monitored, eg, 1 = fraud. There are many more which you can read up on here.

If this cat-and-mouse game continues, perhaps repressive regimes will come to see the futility of trying to censor or block certain websites—much like the music industry vis-a-vis the likes of Napster, e-Mule, etc. So if censorship becomes more difficult, then perhaps launching campaigns of disinformation may be the way to go for authoritarian states; this would dilute attempts at Freedom of Speech 2.0. Open crowdsourcing platforms like Ushahidi are certainly susceptible to misinformation. There's an obvious trade-off: open up entirely, and get more crowdsourced information, but run the risk of some clowns gaming the platform.

But I'd like to argue that falsifying crowdsourced information is perhaps not as easy as one might think, particularly in today's ecosystem where multiple witnesses can report on unfolding events in near real-time. The picture below is a good illustration of this ecosystem in action.

But I'd like to argue that falsifying crowdsourced information is perhaps not as easy as one might think, particularly in today's ecosystem where multiple witnesses can report on unfolding events in near real-time. The picture below is a good illustration of this ecosystem in action.

The fact that crowdsourcing can generate a lot of information is a distinct asset, and one that can be used to weed out disinformation. Take the screenshot below of the Ushahidi-Haiti deployment.

The fact that crowdsourcing can generate a lot of information is a distinct asset, and one that can be used to weed out disinformation. Take the screenshot below of the Ushahidi-Haiti deployment.

Multiple witnesses can be using different technologies to provide a better picture of what is actually happening. The different text messages, pictures, tweets, etc, can be triangulated and validated when they overlap. This prompted my colleague Anand from the New York Times to ask whether the triangulated crisis map might be the new first draft of history? They say that history is written by the winners. Will future history be written by the crowd thanks to Freedom of Speech 2.0?

The above graphic reminds me of Photosynth, which is a neat platform that stitches pictures together to form an overall tableau. This is where Venice comes in. Taking pictures from Flickr or other sources, one can veritably recreate Venice in 3D. Really great stuff. So the question I posed during my TEDx talk last week is, can Ushahidi become the ALLsynth to facilitate Freedom of Speech 2.0? Can we crowdsource crisis information across diverse media and stitch these together to recreate what truly happened—not just over space but across time as well?

Multiple witnesses can be using different technologies to provide a better picture of what is actually happening. The different text messages, pictures, tweets, etc, can be triangulated and validated when they overlap. This prompted my colleague Anand from the New York Times to ask whether the triangulated crisis map might be the new first draft of history? They say that history is written by the winners. Will future history be written by the crowd thanks to Freedom of Speech 2.0?

The above graphic reminds me of Photosynth, which is a neat platform that stitches pictures together to form an overall tableau. This is where Venice comes in. Taking pictures from Flickr or other sources, one can veritably recreate Venice in 3D. Really great stuff. So the question I posed during my TEDx talk last week is, can Ushahidi become the ALLsynth to facilitate Freedom of Speech 2.0? Can we crowdsource crisis information across diverse media and stitch these together to recreate what truly happened—not just over space but across time as well?

And if we could, what would it take to game the Ushahidi ALLsynth system?

And if we could, what would it take to game the Ushahidi ALLsynth system?

- Dozens of pictures from as many different camera phones of an event that never happened.

- Text messages using different wording to describe an event that never happened.

- Tweets (not retweets!).

- Fake blog posts, Facebook groups and Wikipedia entries.

- Fake video footage. Heck, you’d probably want to hack the international media and plant a fake article in the New York Times home page.

- If you really want to go all out, you’d want to get hundreds of (paid?) actors like in The Truman Show.

- You’d likely want to cordon off an entire area of the city or city outskirts.

- Then you’d want to choreograph a few fight scenes with these actors.

- A few rehearsals would probably be in order too.

- Oh and of course props, plus lots of ketchup if you want things to look like they went badly.