[Cross-posted from the Standby Volunteer Task Force Blog]

In the aftermath of some of the recent disasters we witnessed an increasing number of new actors entering the field of international humanitarian response operations. The development of ICTs opened to a variety of individuals and groups unprecedented space for engagement, regardless their physical location and affiliation to traditional responders.

It was predominantly the Haiti earthquake response that pointed out the potential (and limitations) of this volunteer online engagement. Despite the fact that the actual impact, added value and benefit of these emerging initiatives is still being determined and evaluated in order to clearly identify the lessons learned and future steps, some baselines are already obvious and undeniable.

During emergency situations, the very first and the most effective responders are the affected communities themselves. However, for variety of reasons they very often remain unconnected to the traditional emergency response management systems. Simultaneously, with increased access to technology, particularly the mobile and social networks, people will not only spontaneously share information about the meal they had for lunch, but undoubtedly also information about their needs during emergency and crisis situations. Furthermore, the local and international public is seeking innovative ways of engagement in the emergency and humanitarian response.

Simply ignoring such emerging trends would be a short sighted solution – people will be sharing crisis information through any channels available, no matter if the process will be managed by someone or not. This type of information can be potentially transformed into highly valuable real time data that can significantly improve the situational awareness of non-local humanitarian responders, particularly in situations and areas where physical access to the affected community is limited. Similarly, such information sharing can significantly improve the capacity of the communities to rapidly respond to cases of emergency themselves.

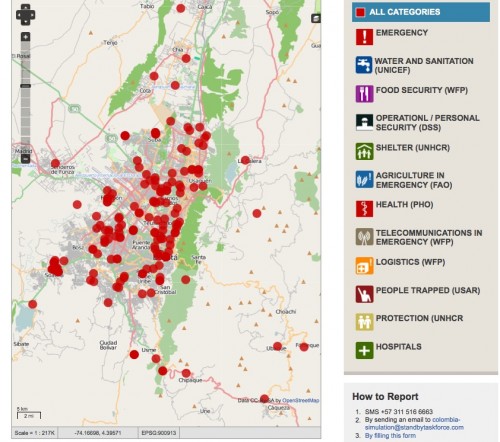

The data processing and mapping based on aggregated reports from the affected population requires capacity, that can hardly be found on the ground and within traditional organizational structures during emergency. The community of online volunteers that is ready to jump-in and provide the lacking capacity could potentially improve significantly the rapidness and effectiveness of the response. The potential is obvious, as well as the challenges that need to be addressed first:

While the SBTF participation in the Colombia Earthquake simulation was widely perceived as successful, the task force has identified a number of key issues that merit further attention. It is important to address these issues to improve the capacity of the SBTF to provide reliable, predictable and sustainable support to disaster-affected communities through coordination with local and international humanitarian responders.

Here is a summary of key findings:

· SBTF’s human capacity should be increased both quantitatively (the current number of volunteers should be at least doubled) and qualitatively (the teams of volunteers have to be trained in variety of fields in order to be able to provide better support).

· The SBTF internal structure should be improved with specific focus on identification and training of team coordinators.

· Deployment and communication protocols need to be further discussed and finalized in close collaboration with the response coordination actors (such as UNOCHA).

· SBTF core team should engage in ongoing discussion with humanitarian responders and other actors in the field of crisis mapping response to ensure that SBTF provides added value to the response operations and does not duplicate efforts of others.

· The SBTF should improve the ability to provide analysis support. The provision of concise analysis to responders during simulation proved very useful in increasing their situational awareness.

· The SBTF should improve the use of automated message translation system which showed very informative results that revealed its ability to expand the volunteer workforce’s capability to prioritize and categorize messages and therefore shortening the time necessary to translate and process reports.

For more detailed description and evaluation of the SBTF deployment see the attached document “Standby Taskforce participation in OCHA Colombia Earthquake Simulation 2010”.

The SBTF volunteers expressed great satisfaction with the exercise and expressed strong interest in further learning and participation in SBTF operations. Also the feedback from responders is positive and confirmed interest in future development of protocols and cooperation.

Whether we like it or, people will use any available channel of communication to share and communicate their situation during crisis. The online crisis mapping volunteer community has a unique opportunity to become a facilitator in this process that can help to turn these conversations into data that are actionable for the humanitarian responders, both local and international. And simultaneously, the volunteer crisis mapping community can respond to the demand of the traditional humanitarian responders who seek the ways to more effectively incorporate the community generated data into their standard operating procedures. The question is not whether the community generated communication is useful or not, the question is HOW to make it useful. The Colombia EQ simulation gave us some valuable ideas what next steps should be taken towards the overall objective that is more effective and accountable communication with crisis affected communities.

Jaroslav Valuch Standby Task Force @jvaluch

While the SBTF participation in the Colombia Earthquake simulation was widely perceived as successful, the task force has identified a number of key issues that merit further attention. It is important to address these issues to improve the capacity of the SBTF to provide reliable, predictable and sustainable support to disaster-affected communities through coordination with local and international humanitarian responders.

Here is a summary of key findings:

· SBTF’s human capacity should be increased both quantitatively (the current number of volunteers should be at least doubled) and qualitatively (the teams of volunteers have to be trained in variety of fields in order to be able to provide better support).

· The SBTF internal structure should be improved with specific focus on identification and training of team coordinators.

· Deployment and communication protocols need to be further discussed and finalized in close collaboration with the response coordination actors (such as UNOCHA).

· SBTF core team should engage in ongoing discussion with humanitarian responders and other actors in the field of crisis mapping response to ensure that SBTF provides added value to the response operations and does not duplicate efforts of others.

· The SBTF should improve the ability to provide analysis support. The provision of concise analysis to responders during simulation proved very useful in increasing their situational awareness.

· The SBTF should improve the use of automated message translation system which showed very informative results that revealed its ability to expand the volunteer workforce’s capability to prioritize and categorize messages and therefore shortening the time necessary to translate and process reports.

For more detailed description and evaluation of the SBTF deployment see the attached document “Standby Taskforce participation in OCHA Colombia Earthquake Simulation 2010”.

The SBTF volunteers expressed great satisfaction with the exercise and expressed strong interest in further learning and participation in SBTF operations. Also the feedback from responders is positive and confirmed interest in future development of protocols and cooperation.

Whether we like it or, people will use any available channel of communication to share and communicate their situation during crisis. The online crisis mapping volunteer community has a unique opportunity to become a facilitator in this process that can help to turn these conversations into data that are actionable for the humanitarian responders, both local and international. And simultaneously, the volunteer crisis mapping community can respond to the demand of the traditional humanitarian responders who seek the ways to more effectively incorporate the community generated data into their standard operating procedures. The question is not whether the community generated communication is useful or not, the question is HOW to make it useful. The Colombia EQ simulation gave us some valuable ideas what next steps should be taken towards the overall objective that is more effective and accountable communication with crisis affected communities.

Jaroslav Valuch Standby Task Force @jvaluch

- How to practically leverage the potential of emergency information that is being shared and communicated by the affected communities and turn it into actionable data that can improve the real-time situational awareness of the local and international responders’ communities?

- How to coordinate and organize the emerging online volunteer crowd and turn it into more reliable and predictable partner for the responders’ community without harming the volunteer nature and genuine flexibility of such initiatives and efforts?

While the SBTF participation in the Colombia Earthquake simulation was widely perceived as successful, the task force has identified a number of key issues that merit further attention. It is important to address these issues to improve the capacity of the SBTF to provide reliable, predictable and sustainable support to disaster-affected communities through coordination with local and international humanitarian responders.

Here is a summary of key findings:

· SBTF’s human capacity should be increased both quantitatively (the current number of volunteers should be at least doubled) and qualitatively (the teams of volunteers have to be trained in variety of fields in order to be able to provide better support).

· The SBTF internal structure should be improved with specific focus on identification and training of team coordinators.

· Deployment and communication protocols need to be further discussed and finalized in close collaboration with the response coordination actors (such as UNOCHA).

· SBTF core team should engage in ongoing discussion with humanitarian responders and other actors in the field of crisis mapping response to ensure that SBTF provides added value to the response operations and does not duplicate efforts of others.

· The SBTF should improve the ability to provide analysis support. The provision of concise analysis to responders during simulation proved very useful in increasing their situational awareness.

· The SBTF should improve the use of automated message translation system which showed very informative results that revealed its ability to expand the volunteer workforce’s capability to prioritize and categorize messages and therefore shortening the time necessary to translate and process reports.

For more detailed description and evaluation of the SBTF deployment see the attached document “Standby Taskforce participation in OCHA Colombia Earthquake Simulation 2010”.

The SBTF volunteers expressed great satisfaction with the exercise and expressed strong interest in further learning and participation in SBTF operations. Also the feedback from responders is positive and confirmed interest in future development of protocols and cooperation.

Whether we like it or, people will use any available channel of communication to share and communicate their situation during crisis. The online crisis mapping volunteer community has a unique opportunity to become a facilitator in this process that can help to turn these conversations into data that are actionable for the humanitarian responders, both local and international. And simultaneously, the volunteer crisis mapping community can respond to the demand of the traditional humanitarian responders who seek the ways to more effectively incorporate the community generated data into their standard operating procedures. The question is not whether the community generated communication is useful or not, the question is HOW to make it useful. The Colombia EQ simulation gave us some valuable ideas what next steps should be taken towards the overall objective that is more effective and accountable communication with crisis affected communities.

Jaroslav Valuch Standby Task Force @jvaluch

While the SBTF participation in the Colombia Earthquake simulation was widely perceived as successful, the task force has identified a number of key issues that merit further attention. It is important to address these issues to improve the capacity of the SBTF to provide reliable, predictable and sustainable support to disaster-affected communities through coordination with local and international humanitarian responders.

Here is a summary of key findings:

· SBTF’s human capacity should be increased both quantitatively (the current number of volunteers should be at least doubled) and qualitatively (the teams of volunteers have to be trained in variety of fields in order to be able to provide better support).

· The SBTF internal structure should be improved with specific focus on identification and training of team coordinators.

· Deployment and communication protocols need to be further discussed and finalized in close collaboration with the response coordination actors (such as UNOCHA).

· SBTF core team should engage in ongoing discussion with humanitarian responders and other actors in the field of crisis mapping response to ensure that SBTF provides added value to the response operations and does not duplicate efforts of others.

· The SBTF should improve the ability to provide analysis support. The provision of concise analysis to responders during simulation proved very useful in increasing their situational awareness.

· The SBTF should improve the use of automated message translation system which showed very informative results that revealed its ability to expand the volunteer workforce’s capability to prioritize and categorize messages and therefore shortening the time necessary to translate and process reports.

For more detailed description and evaluation of the SBTF deployment see the attached document “Standby Taskforce participation in OCHA Colombia Earthquake Simulation 2010”.

The SBTF volunteers expressed great satisfaction with the exercise and expressed strong interest in further learning and participation in SBTF operations. Also the feedback from responders is positive and confirmed interest in future development of protocols and cooperation.

Whether we like it or, people will use any available channel of communication to share and communicate their situation during crisis. The online crisis mapping volunteer community has a unique opportunity to become a facilitator in this process that can help to turn these conversations into data that are actionable for the humanitarian responders, both local and international. And simultaneously, the volunteer crisis mapping community can respond to the demand of the traditional humanitarian responders who seek the ways to more effectively incorporate the community generated data into their standard operating procedures. The question is not whether the community generated communication is useful or not, the question is HOW to make it useful. The Colombia EQ simulation gave us some valuable ideas what next steps should be taken towards the overall objective that is more effective and accountable communication with crisis affected communities.

Jaroslav Valuch Standby Task Force @jvaluch