Last week, I traveled across the country with Liberia’s Peacebuilding Office (PBO) to train county peace committees how to report to the Ushahidi platform. Last night, as we were driving into the sleepy oceanside town of Buchanan, I was reminded of why it is important that these peace committees now exist. My colleague Nat Walker slowed the car as we entered the city limits, looking for any signs of our guesthouse. He pulled over and asked two men walking by, “Where God Bless You?” They nodded and directed us to turn around and look on the right. Nat could see my confusion and told me the house was near a famous checkpoint outside the city. “During the war,” he explained, “many people were fleeing Monrovia. At each checkpoint, if they said or did anything the rebels did not like, they were killed.” So if they made it as far as the Buchanan checkpoint (several hours south of Monrovia), and then through the gate, it was considered a miracle. The Buchanan checkpoint, and the surrounding area, became known as “God Bless You”, in honor of those who made it across.

[caption id="attachment_5673" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="A deserted downtown Buchanan"] [/caption]

Much of Liberia’s identity remains wrapped up in the war that ended a short seven years ago. One of the more promising efforts to heal war wounds and prevent future conflict is the formation of County Peace Committees (CPC). The committees are composed of trusted leaders in the community – youth and elders, men and women – and exist at the district and county level, each one closely linked to nearby police and courts. The initiative started about two years ago and is supported by the United Nations Mission in Liberia’s (UNMIL) Civil Affairs department and the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ Peacebuilding Office. It has taken some time to organize these voluntary committees, but they are now resolving disputes big and small and, this week, were regionally organized to learn early warning incident reporting via the Ushahidi platform.

[caption id="attachment_5674" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="County Peace Committee members gathered in Ganta"]

[/caption]

Much of Liberia’s identity remains wrapped up in the war that ended a short seven years ago. One of the more promising efforts to heal war wounds and prevent future conflict is the formation of County Peace Committees (CPC). The committees are composed of trusted leaders in the community – youth and elders, men and women – and exist at the district and county level, each one closely linked to nearby police and courts. The initiative started about two years ago and is supported by the United Nations Mission in Liberia’s (UNMIL) Civil Affairs department and the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ Peacebuilding Office. It has taken some time to organize these voluntary committees, but they are now resolving disputes big and small and, this week, were regionally organized to learn early warning incident reporting via the Ushahidi platform.

[caption id="attachment_5674" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="County Peace Committee members gathered in Ganta"] [/caption]

This week’s trainings were held in four different regions of Liberia with 73 CPC focal persons in attendance. When we reached the Ushahidi portion of the training, CPC members were quick to catch on to the utility of the platform. I have found that when I explain how the tool has been used in other settings to report conflict, peacebuilders throughout Liberia immediately relate to the need for more reliable and rapid methods of disseminating information as conflict is breaking out. When I show pictures of the post-election violence in Kenya, or the DRC map populated with SGBV reports, there is a knowing concern on people’s faces that yes, these are familiar situations and no, we do not have all the tools we need to be informed. Even more important, in the context of Liberia, peace committee members are seeking methods to identify instability before actual conflict erupts; they know from experience that a fire spreads quickly once all of the conditions are present to light it.

[caption id="attachment_5675" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC members in Buchanan learning the Ushahidi platform"]

[/caption]

This week’s trainings were held in four different regions of Liberia with 73 CPC focal persons in attendance. When we reached the Ushahidi portion of the training, CPC members were quick to catch on to the utility of the platform. I have found that when I explain how the tool has been used in other settings to report conflict, peacebuilders throughout Liberia immediately relate to the need for more reliable and rapid methods of disseminating information as conflict is breaking out. When I show pictures of the post-election violence in Kenya, or the DRC map populated with SGBV reports, there is a knowing concern on people’s faces that yes, these are familiar situations and no, we do not have all the tools we need to be informed. Even more important, in the context of Liberia, peace committee members are seeking methods to identify instability before actual conflict erupts; they know from experience that a fire spreads quickly once all of the conditions are present to light it.

[caption id="attachment_5675" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC members in Buchanan learning the Ushahidi platform"] [/caption]

During each of this week’s trainings, I introduced the concept behind the Ushahidi platform and then conducted a simulation where members sent in sample SMS describing the kind of issues they often encounter. Together, we looked at the PBO instance’s backend to see messages coming in and evaluated the contents of each message to see if it was “mappable”. This is usually where I found a gap between participants’ conceptual understanding and their ability to use the necessary technology to send information to the platform.

[caption id="attachment_5676" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC elders seeing Ushahidi for the first time"]

[/caption]

During each of this week’s trainings, I introduced the concept behind the Ushahidi platform and then conducted a simulation where members sent in sample SMS describing the kind of issues they often encounter. Together, we looked at the PBO instance’s backend to see messages coming in and evaluated the contents of each message to see if it was “mappable”. This is usually where I found a gap between participants’ conceptual understanding and their ability to use the necessary technology to send information to the platform.

[caption id="attachment_5676" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC elders seeing Ushahidi for the first time"] [/caption]

A good example came from our session in Buchanan. When we came to the simulation, I asked how many people send one or more texts per week; two of 12 people raised their hands. How about one per month? One person. Judging by the silence of the remaining nine people, I conducted an impromptu intro to texting: how to create a message, change the predictive text setting, delete and insert punctuation and send. Much to my surprise, most participants were riveted – responding to the basic instructions as if learning them for the first time. Afterwards we sent simulation texts, sharing the four phones participants had among them. Those who were the most proficient with texting (two participants) took 15 minutes to send one message. Those who were new to texting took 20-25 minutes with one-on-one instruction. Here are a couple of text examples from the simulation:

1. "100pm there was fighting number 2 compound in vedier town grand bassa county" (20 minutes, new texter)

2. "There is a growing threat of electoral violence in Liberia, where young people are divided on political lines. Two days ago in the city of Buchanan, there was a brutal fight between groups of young people on the 27 of Sept at about 12.00am" (15 minutes, experienced texter)

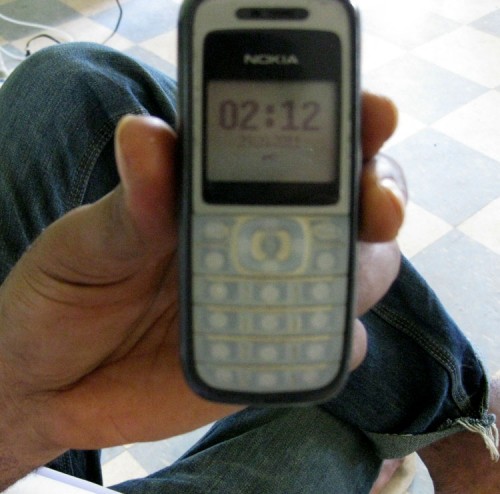

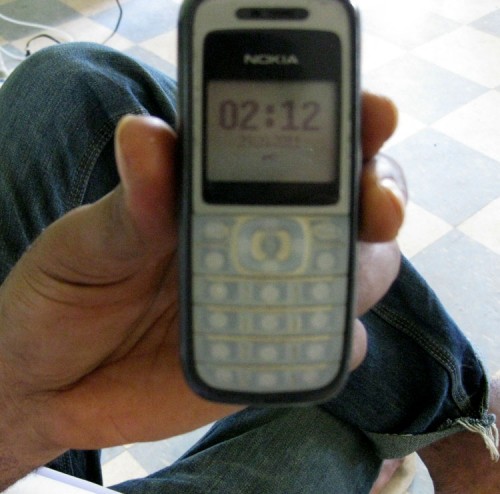

To complicate matters, some participants had phones like the one pictured below that had been so completely worn down that some or all of the numbers and letters were gone.

[caption id="attachment_5677" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="A well-worn phone without numbers or letters"]

[/caption]

A good example came from our session in Buchanan. When we came to the simulation, I asked how many people send one or more texts per week; two of 12 people raised their hands. How about one per month? One person. Judging by the silence of the remaining nine people, I conducted an impromptu intro to texting: how to create a message, change the predictive text setting, delete and insert punctuation and send. Much to my surprise, most participants were riveted – responding to the basic instructions as if learning them for the first time. Afterwards we sent simulation texts, sharing the four phones participants had among them. Those who were the most proficient with texting (two participants) took 15 minutes to send one message. Those who were new to texting took 20-25 minutes with one-on-one instruction. Here are a couple of text examples from the simulation:

1. "100pm there was fighting number 2 compound in vedier town grand bassa county" (20 minutes, new texter)

2. "There is a growing threat of electoral violence in Liberia, where young people are divided on political lines. Two days ago in the city of Buchanan, there was a brutal fight between groups of young people on the 27 of Sept at about 12.00am" (15 minutes, experienced texter)

To complicate matters, some participants had phones like the one pictured below that had been so completely worn down that some or all of the numbers and letters were gone.

[caption id="attachment_5677" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="A well-worn phone without numbers or letters"] [/caption]

Sometimes it is a mystery unraveling the reasons why certain people in the room can send a message and others cannot. When I spoke with my colleague conducting a similar training this week, he said several participants sent detailed messages and in a shorter timeframe - 10 minutes. The same was true of our training in Monrovia, where about 60% of the members sent messages in 10 minutes (the rest in 15-20). There seemed to be a positive correlation between participants from larger population centers and their ability to text. There was also a clear divide between the older participants and the youth; those under 35 were generally more familiar with texting or picked it up more quickly.

[caption id="attachment_5678" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC members teaching each other how to text"]

[/caption]

Sometimes it is a mystery unraveling the reasons why certain people in the room can send a message and others cannot. When I spoke with my colleague conducting a similar training this week, he said several participants sent detailed messages and in a shorter timeframe - 10 minutes. The same was true of our training in Monrovia, where about 60% of the members sent messages in 10 minutes (the rest in 15-20). There seemed to be a positive correlation between participants from larger population centers and their ability to text. There was also a clear divide between the older participants and the youth; those under 35 were generally more familiar with texting or picked it up more quickly.

[caption id="attachment_5678" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC members teaching each other how to text"] [/caption]

Another trend within the CPCs is that many participants were elders or middle-aged; they started their peacebuilding work at the beginning of the fourteen-year civil war and, while these peacebuilding veterans are now well-equipped to lead CPCs, their age group is less familiar with SMS. And here's an interesting assumption that many of us might have also made: when the PBO was recruiting CPC focal persons to attend these trainings, they specifically asked for individuals who could read and write, thinking this meant they could also text. If it were simply a matter of learning a new skill, then the trainings could serve to introduce texting; but with hardly any emphasis on critical thinking in Liberia’s education system, it becomes markedly more difficult to transfer such a skill.

[caption id="attachment_5680" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="Nat Walker of the Peacebuilding Office shows CPC members how to text"]

[/caption]

Another trend within the CPCs is that many participants were elders or middle-aged; they started their peacebuilding work at the beginning of the fourteen-year civil war and, while these peacebuilding veterans are now well-equipped to lead CPCs, their age group is less familiar with SMS. And here's an interesting assumption that many of us might have also made: when the PBO was recruiting CPC focal persons to attend these trainings, they specifically asked for individuals who could read and write, thinking this meant they could also text. If it were simply a matter of learning a new skill, then the trainings could serve to introduce texting; but with hardly any emphasis on critical thinking in Liberia’s education system, it becomes markedly more difficult to transfer such a skill.

[caption id="attachment_5680" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="Nat Walker of the Peacebuilding Office shows CPC members how to text"] [/caption]

But Liberia's education system is not the only reason why texting might prove difficult for CPC members. It’s a simple truth that only so many leaps can be made at once. When I first started using the Internet as a teenager, I only used email – it didn’t occur to me to do anything else. And while more exposure and familiarity with the Internet has changed the way I use it, there were many other factors at play: I owned my own computer, my Internet connection was fast and reliable, my education and upbringing encouraged me to investigate and play when I didn’t understand a new tool, and my peers were doing the same exploring and experimenting. In the case of many Liberians attending the CPC trainings, the following was true: they shared ownership of one phone with their family or entire community, the phone was left on charge at a local charge shop for long periods, they lived in a place with spotty network coverage, credit is added to the phone sparingly and calls or messages are not made without considering the cost, and participants’ education and access to technology were disrupted by more than a decade of war. The conditions that need to be present to text in Liberia do not necessarily exist simply because someone has access to a phone; if there is one major assumption that many of us in ICT for development are guilty of, it’s this one.

[caption id="attachment_5681" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC member shows off his "how to text to Ushahidi" card"]

[/caption]

But Liberia's education system is not the only reason why texting might prove difficult for CPC members. It’s a simple truth that only so many leaps can be made at once. When I first started using the Internet as a teenager, I only used email – it didn’t occur to me to do anything else. And while more exposure and familiarity with the Internet has changed the way I use it, there were many other factors at play: I owned my own computer, my Internet connection was fast and reliable, my education and upbringing encouraged me to investigate and play when I didn’t understand a new tool, and my peers were doing the same exploring and experimenting. In the case of many Liberians attending the CPC trainings, the following was true: they shared ownership of one phone with their family or entire community, the phone was left on charge at a local charge shop for long periods, they lived in a place with spotty network coverage, credit is added to the phone sparingly and calls or messages are not made without considering the cost, and participants’ education and access to technology were disrupted by more than a decade of war. The conditions that need to be present to text in Liberia do not necessarily exist simply because someone has access to a phone; if there is one major assumption that many of us in ICT for development are guilty of, it’s this one.

[caption id="attachment_5681" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC member shows off his "how to text to Ushahidi" card"] [/caption]

But here’s the good news. After hours of “texting 101” sessions and practice simulations, I asked each exhausted group of participants if they could now send texts whenever something unsettling happened in their communities. “We can make it!” one elder said emphatically; “I am overwhelmed that I can now text” remarked another man with a big smile, who was already composing his first SMS to his teenage daughter. And since the trainings, many have made it: we have received 20 early-warning texts in the last three days from these participants. This is a reminder of what must be present, perhaps above all else, to learn a new skill: motivation.

[/caption]

But here’s the good news. After hours of “texting 101” sessions and practice simulations, I asked each exhausted group of participants if they could now send texts whenever something unsettling happened in their communities. “We can make it!” one elder said emphatically; “I am overwhelmed that I can now text” remarked another man with a big smile, who was already composing his first SMS to his teenage daughter. And since the trainings, many have made it: we have received 20 early-warning texts in the last three days from these participants. This is a reminder of what must be present, perhaps above all else, to learn a new skill: motivation.

[/caption]

Much of Liberia’s identity remains wrapped up in the war that ended a short seven years ago. One of the more promising efforts to heal war wounds and prevent future conflict is the formation of County Peace Committees (CPC). The committees are composed of trusted leaders in the community – youth and elders, men and women – and exist at the district and county level, each one closely linked to nearby police and courts. The initiative started about two years ago and is supported by the United Nations Mission in Liberia’s (UNMIL) Civil Affairs department and the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ Peacebuilding Office. It has taken some time to organize these voluntary committees, but they are now resolving disputes big and small and, this week, were regionally organized to learn early warning incident reporting via the Ushahidi platform.

[caption id="attachment_5674" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="County Peace Committee members gathered in Ganta"]

[/caption]

Much of Liberia’s identity remains wrapped up in the war that ended a short seven years ago. One of the more promising efforts to heal war wounds and prevent future conflict is the formation of County Peace Committees (CPC). The committees are composed of trusted leaders in the community – youth and elders, men and women – and exist at the district and county level, each one closely linked to nearby police and courts. The initiative started about two years ago and is supported by the United Nations Mission in Liberia’s (UNMIL) Civil Affairs department and the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ Peacebuilding Office. It has taken some time to organize these voluntary committees, but they are now resolving disputes big and small and, this week, were regionally organized to learn early warning incident reporting via the Ushahidi platform.

[caption id="attachment_5674" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="County Peace Committee members gathered in Ganta"] [/caption]

This week’s trainings were held in four different regions of Liberia with 73 CPC focal persons in attendance. When we reached the Ushahidi portion of the training, CPC members were quick to catch on to the utility of the platform. I have found that when I explain how the tool has been used in other settings to report conflict, peacebuilders throughout Liberia immediately relate to the need for more reliable and rapid methods of disseminating information as conflict is breaking out. When I show pictures of the post-election violence in Kenya, or the DRC map populated with SGBV reports, there is a knowing concern on people’s faces that yes, these are familiar situations and no, we do not have all the tools we need to be informed. Even more important, in the context of Liberia, peace committee members are seeking methods to identify instability before actual conflict erupts; they know from experience that a fire spreads quickly once all of the conditions are present to light it.

[caption id="attachment_5675" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC members in Buchanan learning the Ushahidi platform"]

[/caption]

This week’s trainings were held in four different regions of Liberia with 73 CPC focal persons in attendance. When we reached the Ushahidi portion of the training, CPC members were quick to catch on to the utility of the platform. I have found that when I explain how the tool has been used in other settings to report conflict, peacebuilders throughout Liberia immediately relate to the need for more reliable and rapid methods of disseminating information as conflict is breaking out. When I show pictures of the post-election violence in Kenya, or the DRC map populated with SGBV reports, there is a knowing concern on people’s faces that yes, these are familiar situations and no, we do not have all the tools we need to be informed. Even more important, in the context of Liberia, peace committee members are seeking methods to identify instability before actual conflict erupts; they know from experience that a fire spreads quickly once all of the conditions are present to light it.

[caption id="attachment_5675" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC members in Buchanan learning the Ushahidi platform"] [/caption]

During each of this week’s trainings, I introduced the concept behind the Ushahidi platform and then conducted a simulation where members sent in sample SMS describing the kind of issues they often encounter. Together, we looked at the PBO instance’s backend to see messages coming in and evaluated the contents of each message to see if it was “mappable”. This is usually where I found a gap between participants’ conceptual understanding and their ability to use the necessary technology to send information to the platform.

[caption id="attachment_5676" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC elders seeing Ushahidi for the first time"]

[/caption]

During each of this week’s trainings, I introduced the concept behind the Ushahidi platform and then conducted a simulation where members sent in sample SMS describing the kind of issues they often encounter. Together, we looked at the PBO instance’s backend to see messages coming in and evaluated the contents of each message to see if it was “mappable”. This is usually where I found a gap between participants’ conceptual understanding and their ability to use the necessary technology to send information to the platform.

[caption id="attachment_5676" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC elders seeing Ushahidi for the first time"] [/caption]

A good example came from our session in Buchanan. When we came to the simulation, I asked how many people send one or more texts per week; two of 12 people raised their hands. How about one per month? One person. Judging by the silence of the remaining nine people, I conducted an impromptu intro to texting: how to create a message, change the predictive text setting, delete and insert punctuation and send. Much to my surprise, most participants were riveted – responding to the basic instructions as if learning them for the first time. Afterwards we sent simulation texts, sharing the four phones participants had among them. Those who were the most proficient with texting (two participants) took 15 minutes to send one message. Those who were new to texting took 20-25 minutes with one-on-one instruction. Here are a couple of text examples from the simulation:

1. "100pm there was fighting number 2 compound in vedier town grand bassa county" (20 minutes, new texter)

2. "There is a growing threat of electoral violence in Liberia, where young people are divided on political lines. Two days ago in the city of Buchanan, there was a brutal fight between groups of young people on the 27 of Sept at about 12.00am" (15 minutes, experienced texter)

To complicate matters, some participants had phones like the one pictured below that had been so completely worn down that some or all of the numbers and letters were gone.

[caption id="attachment_5677" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="A well-worn phone without numbers or letters"]

[/caption]

A good example came from our session in Buchanan. When we came to the simulation, I asked how many people send one or more texts per week; two of 12 people raised their hands. How about one per month? One person. Judging by the silence of the remaining nine people, I conducted an impromptu intro to texting: how to create a message, change the predictive text setting, delete and insert punctuation and send. Much to my surprise, most participants were riveted – responding to the basic instructions as if learning them for the first time. Afterwards we sent simulation texts, sharing the four phones participants had among them. Those who were the most proficient with texting (two participants) took 15 minutes to send one message. Those who were new to texting took 20-25 minutes with one-on-one instruction. Here are a couple of text examples from the simulation:

1. "100pm there was fighting number 2 compound in vedier town grand bassa county" (20 minutes, new texter)

2. "There is a growing threat of electoral violence in Liberia, where young people are divided on political lines. Two days ago in the city of Buchanan, there was a brutal fight between groups of young people on the 27 of Sept at about 12.00am" (15 minutes, experienced texter)

To complicate matters, some participants had phones like the one pictured below that had been so completely worn down that some or all of the numbers and letters were gone.

[caption id="attachment_5677" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="A well-worn phone without numbers or letters"] [/caption]

Sometimes it is a mystery unraveling the reasons why certain people in the room can send a message and others cannot. When I spoke with my colleague conducting a similar training this week, he said several participants sent detailed messages and in a shorter timeframe - 10 minutes. The same was true of our training in Monrovia, where about 60% of the members sent messages in 10 minutes (the rest in 15-20). There seemed to be a positive correlation between participants from larger population centers and their ability to text. There was also a clear divide between the older participants and the youth; those under 35 were generally more familiar with texting or picked it up more quickly.

[caption id="attachment_5678" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC members teaching each other how to text"]

[/caption]

Sometimes it is a mystery unraveling the reasons why certain people in the room can send a message and others cannot. When I spoke with my colleague conducting a similar training this week, he said several participants sent detailed messages and in a shorter timeframe - 10 minutes. The same was true of our training in Monrovia, where about 60% of the members sent messages in 10 minutes (the rest in 15-20). There seemed to be a positive correlation between participants from larger population centers and their ability to text. There was also a clear divide between the older participants and the youth; those under 35 were generally more familiar with texting or picked it up more quickly.

[caption id="attachment_5678" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC members teaching each other how to text"] [/caption]

Another trend within the CPCs is that many participants were elders or middle-aged; they started their peacebuilding work at the beginning of the fourteen-year civil war and, while these peacebuilding veterans are now well-equipped to lead CPCs, their age group is less familiar with SMS. And here's an interesting assumption that many of us might have also made: when the PBO was recruiting CPC focal persons to attend these trainings, they specifically asked for individuals who could read and write, thinking this meant they could also text. If it were simply a matter of learning a new skill, then the trainings could serve to introduce texting; but with hardly any emphasis on critical thinking in Liberia’s education system, it becomes markedly more difficult to transfer such a skill.

[caption id="attachment_5680" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="Nat Walker of the Peacebuilding Office shows CPC members how to text"]

[/caption]

Another trend within the CPCs is that many participants were elders or middle-aged; they started their peacebuilding work at the beginning of the fourteen-year civil war and, while these peacebuilding veterans are now well-equipped to lead CPCs, their age group is less familiar with SMS. And here's an interesting assumption that many of us might have also made: when the PBO was recruiting CPC focal persons to attend these trainings, they specifically asked for individuals who could read and write, thinking this meant they could also text. If it were simply a matter of learning a new skill, then the trainings could serve to introduce texting; but with hardly any emphasis on critical thinking in Liberia’s education system, it becomes markedly more difficult to transfer such a skill.

[caption id="attachment_5680" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="Nat Walker of the Peacebuilding Office shows CPC members how to text"] [/caption]

But Liberia's education system is not the only reason why texting might prove difficult for CPC members. It’s a simple truth that only so many leaps can be made at once. When I first started using the Internet as a teenager, I only used email – it didn’t occur to me to do anything else. And while more exposure and familiarity with the Internet has changed the way I use it, there were many other factors at play: I owned my own computer, my Internet connection was fast and reliable, my education and upbringing encouraged me to investigate and play when I didn’t understand a new tool, and my peers were doing the same exploring and experimenting. In the case of many Liberians attending the CPC trainings, the following was true: they shared ownership of one phone with their family or entire community, the phone was left on charge at a local charge shop for long periods, they lived in a place with spotty network coverage, credit is added to the phone sparingly and calls or messages are not made without considering the cost, and participants’ education and access to technology were disrupted by more than a decade of war. The conditions that need to be present to text in Liberia do not necessarily exist simply because someone has access to a phone; if there is one major assumption that many of us in ICT for development are guilty of, it’s this one.

[caption id="attachment_5681" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC member shows off his "how to text to Ushahidi" card"]

[/caption]

But Liberia's education system is not the only reason why texting might prove difficult for CPC members. It’s a simple truth that only so many leaps can be made at once. When I first started using the Internet as a teenager, I only used email – it didn’t occur to me to do anything else. And while more exposure and familiarity with the Internet has changed the way I use it, there were many other factors at play: I owned my own computer, my Internet connection was fast and reliable, my education and upbringing encouraged me to investigate and play when I didn’t understand a new tool, and my peers were doing the same exploring and experimenting. In the case of many Liberians attending the CPC trainings, the following was true: they shared ownership of one phone with their family or entire community, the phone was left on charge at a local charge shop for long periods, they lived in a place with spotty network coverage, credit is added to the phone sparingly and calls or messages are not made without considering the cost, and participants’ education and access to technology were disrupted by more than a decade of war. The conditions that need to be present to text in Liberia do not necessarily exist simply because someone has access to a phone; if there is one major assumption that many of us in ICT for development are guilty of, it’s this one.

[caption id="attachment_5681" align="aligncenter" width="500" caption="CPC member shows off his "how to text to Ushahidi" card"] [/caption]

But here’s the good news. After hours of “texting 101” sessions and practice simulations, I asked each exhausted group of participants if they could now send texts whenever something unsettling happened in their communities. “We can make it!” one elder said emphatically; “I am overwhelmed that I can now text” remarked another man with a big smile, who was already composing his first SMS to his teenage daughter. And since the trainings, many have made it: we have received 20 early-warning texts in the last three days from these participants. This is a reminder of what must be present, perhaps above all else, to learn a new skill: motivation.

[/caption]

But here’s the good news. After hours of “texting 101” sessions and practice simulations, I asked each exhausted group of participants if they could now send texts whenever something unsettling happened in their communities. “We can make it!” one elder said emphatically; “I am overwhelmed that I can now text” remarked another man with a big smile, who was already composing his first SMS to his teenage daughter. And since the trainings, many have made it: we have received 20 early-warning texts in the last three days from these participants. This is a reminder of what must be present, perhaps above all else, to learn a new skill: motivation.