[Guest post by Francesco Bartoli. Francesco is the founder at Geobeyond Srl and a geospatial technologist who fosters innovation technology to Geographic Information System and Spatial Data Infrastructure. He is advocate of Open Source, Open Government, Open Data development where also acts as OGC standards and INSPIRE advisor to assisting business programs at largest extent of interoperability and cooperation.]

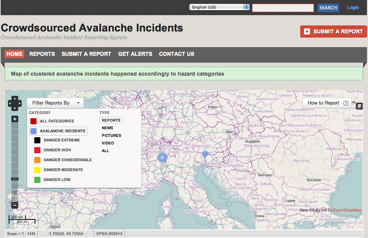

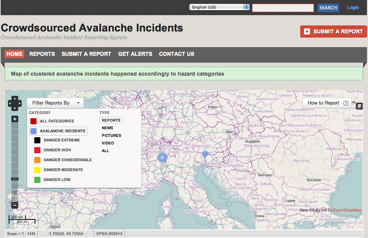

Avalanches are a serious problem for mountaineers during their tours in the wilderness but lately they are increasingly happening much more also as natural phenomena due to uncommon snowfalls. More often they are being triggered in the neighbourhood of ski-areas by off-piste venture causing deaths and damages. Here we present a crowdsourcing initiative, based on the social mapping tool Ushahidi, aiming at improving avalanche awareness by capturing incidents from the practitioners and making such data freely reusable for a variety of large-scale applications.

http://geoavalanche.org/incident/

Fig. 1: Danger Level for an avalanche bulletin in a geographic area

Currently the most recent practices from professional rescue shows how self-rescue procedures are the sole proficient way to save lives when an avalanche buries some people, since the struggle is strongly time-dependent in order to being effectively decisive in. This can exclusively happen when practitioners have at their disposal the necessary equipment to find and dig someone out of an avalanche: ARTVA, shovel and probe. Nowadays, with the improvements reached on the new generation of beacons, rescue operations become quicker but often this is not easily enough. The knowledge of procedures and training on how to self-rescue has to be addressed in the community as much largely as possible to raise successful results when a such crisis happens.

Any incident is subjected to a further inspection when the professional rescue is claimed to an avalanche scene and the information related to are treated respectfully in a manner that follows regulations and operative procedures of reference. As a result all those details are captured as expected by the national Avalanche Warning Services, which collect incidents worldwide for driving avalanche awareness and prevention in each country. This scenario figures out the need of an innovative spatially aware tool for mapping such information which could be used for statistical purposes and mitigation measures and much more important to handle also avalanche incidents that are still remaining hidden.

Therefore, from a geographical perspective, the process of data capturing has to be addressed in a way that meets the spatial context of an avalanche incident. The power of Ushahidi is to make easily this job in order to meet how stakeholders are structuring this information and potentially to make democratized and valuable those data coming from crowdsourcing participation.

Avalanche incidents data were analyzed in order to being structured as well as compared with standards in use by Avalanche Warning Service worldwide. The benefits of using Ushahidi go beyond to developing an historical and extended database of avalanche incidents happened during years publicly available in the form of thematic maps and also as API RESTful mechanism for accessing data by citizens, stakeholders and governments.

Fig. 1: Danger Level for an avalanche bulletin in a geographic area

Currently the most recent practices from professional rescue shows how self-rescue procedures are the sole proficient way to save lives when an avalanche buries some people, since the struggle is strongly time-dependent in order to being effectively decisive in. This can exclusively happen when practitioners have at their disposal the necessary equipment to find and dig someone out of an avalanche: ARTVA, shovel and probe. Nowadays, with the improvements reached on the new generation of beacons, rescue operations become quicker but often this is not easily enough. The knowledge of procedures and training on how to self-rescue has to be addressed in the community as much largely as possible to raise successful results when a such crisis happens.

Any incident is subjected to a further inspection when the professional rescue is claimed to an avalanche scene and the information related to are treated respectfully in a manner that follows regulations and operative procedures of reference. As a result all those details are captured as expected by the national Avalanche Warning Services, which collect incidents worldwide for driving avalanche awareness and prevention in each country. This scenario figures out the need of an innovative spatially aware tool for mapping such information which could be used for statistical purposes and mitigation measures and much more important to handle also avalanche incidents that are still remaining hidden.

Therefore, from a geographical perspective, the process of data capturing has to be addressed in a way that meets the spatial context of an avalanche incident. The power of Ushahidi is to make easily this job in order to meet how stakeholders are structuring this information and potentially to make democratized and valuable those data coming from crowdsourcing participation.

Avalanche incidents data were analyzed in order to being structured as well as compared with standards in use by Avalanche Warning Service worldwide. The benefits of using Ushahidi go beyond to developing an historical and extended database of avalanche incidents happened during years publicly available in the form of thematic maps and also as API RESTful mechanism for accessing data by citizens, stakeholders and governments.

Introduction

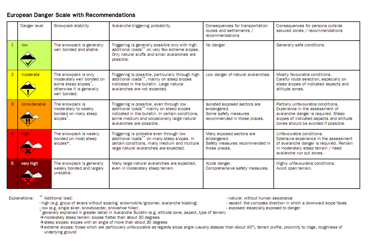

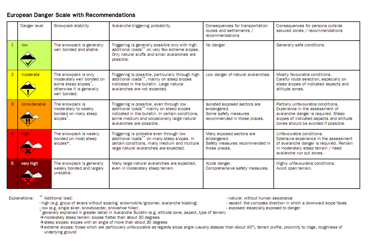

In recent decades back country tourism in the mountain area, during the winter, have led to a significant increase in the number of practitioners who tackle snowy paths or land prone to avalanche slide. This, often, is not commensurate with a quite equally preparedness in the evaluation of meteorological conditions and snowpack’s stability to deal with, which is the fundamental step towards a safe trip. Despite exposure to avalanches is a variable dependent by many factors, including some unpredictable, often the lack of the necessary experience combined with a poor consideration of avalanche bulletins, makes snowy terrain potentially subject to such phenomena. In addition, the unpredictability of some events related to the stratification of the soil results that even in situations where you keep all the most safe conducts and although the risk may be at a level significantly low in the danger’s scale (5 –VERY HIGH, 4 – HIGH, 3 – CONSIDERABLE, 2 – MODERATE, 1 – LOW), the detachment of an avalanche is a phenomenon, which can continuously still happen. Especially while there always might be some discrepancy between local situations and areas of interest of an avalanche bulletin. Fig. 1: Danger Level for an avalanche bulletin in a geographic area

Currently the most recent practices from professional rescue shows how self-rescue procedures are the sole proficient way to save lives when an avalanche buries some people, since the struggle is strongly time-dependent in order to being effectively decisive in. This can exclusively happen when practitioners have at their disposal the necessary equipment to find and dig someone out of an avalanche: ARTVA, shovel and probe. Nowadays, with the improvements reached on the new generation of beacons, rescue operations become quicker but often this is not easily enough. The knowledge of procedures and training on how to self-rescue has to be addressed in the community as much largely as possible to raise successful results when a such crisis happens.

Any incident is subjected to a further inspection when the professional rescue is claimed to an avalanche scene and the information related to are treated respectfully in a manner that follows regulations and operative procedures of reference. As a result all those details are captured as expected by the national Avalanche Warning Services, which collect incidents worldwide for driving avalanche awareness and prevention in each country. This scenario figures out the need of an innovative spatially aware tool for mapping such information which could be used for statistical purposes and mitigation measures and much more important to handle also avalanche incidents that are still remaining hidden.

Therefore, from a geographical perspective, the process of data capturing has to be addressed in a way that meets the spatial context of an avalanche incident. The power of Ushahidi is to make easily this job in order to meet how stakeholders are structuring this information and potentially to make democratized and valuable those data coming from crowdsourcing participation.

Avalanche incidents data were analyzed in order to being structured as well as compared with standards in use by Avalanche Warning Service worldwide. The benefits of using Ushahidi go beyond to developing an historical and extended database of avalanche incidents happened during years publicly available in the form of thematic maps and also as API RESTful mechanism for accessing data by citizens, stakeholders and governments.

Fig. 1: Danger Level for an avalanche bulletin in a geographic area

Currently the most recent practices from professional rescue shows how self-rescue procedures are the sole proficient way to save lives when an avalanche buries some people, since the struggle is strongly time-dependent in order to being effectively decisive in. This can exclusively happen when practitioners have at their disposal the necessary equipment to find and dig someone out of an avalanche: ARTVA, shovel and probe. Nowadays, with the improvements reached on the new generation of beacons, rescue operations become quicker but often this is not easily enough. The knowledge of procedures and training on how to self-rescue has to be addressed in the community as much largely as possible to raise successful results when a such crisis happens.

Any incident is subjected to a further inspection when the professional rescue is claimed to an avalanche scene and the information related to are treated respectfully in a manner that follows regulations and operative procedures of reference. As a result all those details are captured as expected by the national Avalanche Warning Services, which collect incidents worldwide for driving avalanche awareness and prevention in each country. This scenario figures out the need of an innovative spatially aware tool for mapping such information which could be used for statistical purposes and mitigation measures and much more important to handle also avalanche incidents that are still remaining hidden.

Therefore, from a geographical perspective, the process of data capturing has to be addressed in a way that meets the spatial context of an avalanche incident. The power of Ushahidi is to make easily this job in order to meet how stakeholders are structuring this information and potentially to make democratized and valuable those data coming from crowdsourcing participation.

Avalanche incidents data were analyzed in order to being structured as well as compared with standards in use by Avalanche Warning Service worldwide. The benefits of using Ushahidi go beyond to developing an historical and extended database of avalanche incidents happened during years publicly available in the form of thematic maps and also as API RESTful mechanism for accessing data by citizens, stakeholders and governments.

Using Ushahidi to model reports for avalanche incidents

This general explanation above figures out how the problem has been issued and why the initiative of Geoavalanche - a project born from the collaborative efforts by Geobeyond with mountain’s passion in mind - would leverage the awareness of risk using new forms of sustainable democratization over the Web 2.0. Geoavalanche aims at supporting the safety across mountains through the development of tools to better sharing avalanche information and data over the Internet. Maps are an approach to highlight new phenomena and display results in an easily understandable way. The idea behind this initiative is to harness the benefits of crowdsourcing information around avalanche incidents (making use of a large group of people being able to report on a story) and smoothly assist the sharing of knowledge in an environment where rumors and uncertainty were predominant. Geoavalanche site uses Ushahidi platform for reporting incidents originated by an avalanche that may have been originated by a natural or human behavior. People can basically perform the following operations:- Viewing all reports of incidents happened and verified in a map since the launch of the website;

- Selecting reports by categories identified as the different levels of avalanche danger’s scale at which each incident occurred;

- Reporting a new incident by providing a minimal set of information;

- Subscribing for being alerted by e-mail or SMS on new incidents occurred nearby a chosen area;

- Browsing the map at different scales for geographically clustered incidents over larger areas (National, Continental detail);

- Viewing statistically chart of incidents by years, zones, etc.

- The category of each single report which corresponds to the current hazard level (totally complaint with the level and color of the international danger’s standard scale) emitted with the bulletin by the national Avalanche Warning System for a certain area of interest;

- The activities that mountaineers were doing when the incident happened (Skitouring, snowshoeing, skiing off-piste, snowmobiling, etc);

- The mountain where each incident happened;

- The aspect where the avalanche has been triggered;

- The number of buried, injured and fatalities caused by such avalanche;

- Some possible links to news and images related to the specific incident.

- The slope of the terrain where it happened;

- The avalanche path taken in meters by the front from the slab point;

- What kind of safety gears the team was equipped (optional also for base users);

- The cause of the detachment.

Social impact for avalanche geodata

This social work is basically an experiment that would outcome effects as much possible as extended in a world where spatial information is not still diffused. Geoavalanche would expect to improve the educational use of such spatially enable data and help organizations and governments to better understand how the involvement of citizenship can be crucial for leveraging a real problem. In fact, basically, there were two different promising approaches, which have been worthwhile to issue:- The emerge of hidden incidents that usually are going to geographically disappear;

- The valuable combination of being able to report such information with a more socialize manner (with mobility in mind) as much as this would fit with many young people who are going in the wilderness.

- Submitting the reports on a mobile application, available both for iOS and Android users;

- Tweeting with special hashtag inserted in the body of a post on Twitter (#geoavalanche - #avalreport - #avalevent);

- Emailing with the description of the story;

- Filling the forms on the submitting page.